Introduction

Why is it that separating a classroom into two groups and having them compete for a prize can lead to children developing ill feelings toward those of the opposing group? What happens when a child feels as if they don't belong to their own group? Does this relationship matter? The answer is yes. Previous studies have found that how one identifies with their group affects both the emotions and the behaviors of those involved; however, there is still a considerable lack of studies investigating the relationship between factors such as group roles and positively/negatively experienced emotions. Our study focuses on the influence of two potential factors: type of role one holds and the environment (supportive or hostile). To understand the potential impacts of these two factors, we must first explore previous findings on group membership.

According to Hogg et al. (as cited in Mackie & Smith, 2020), an individual's relationship with their respective group plays an important role in their life both socially and psychologically. This relationship can serve to increase their self-esteem, reduce uncertainty, and foster a sense of belonging and connectedness with others who identify to be a part of the group. The degree to which an individual identifies themselves as belonging to a group varies based on how similar they are to the in-group and how attached one feels to other members (Leach et al., 2008).

Past research has demonstrated one way in which people appear to categorize themselves in terms of their group. Turner et al.'s (1987, as cited in Leach et al., 2008) self-categorization theory suggests that an individual’s group becomes a central aspect of their self-concept. One way an individual can self-categorize themselves is by "depersonalizing" their own self-perception, and instead self-stereotyping themselves. By self-stereotyping themselves, individuals feel more closely attached to their in-group members as they view themselves to be similar to them. As a result of this process, these individuals are able to emotionally share their in-group's achievements and losses with other members in their group (Lewin, 1948; Tajfel, 1978, as cited in Leach et al. 2008). Lewin (1948, as cited in Leach et al., 2008) on the other hand, suggested that the people who closely identify themselves with an in-group are highly likely to feel a psychological bond. In this way, members of the in-group have a personal and individual sense of self at the group level instead of depriving their personal sense of identity as Turner suggested. Turner et al. (1987, as cited in Leach et al., 2008) ultimately believed that this centrality of an individual's in-group membership would make them sensitive to intergroup events, causing them to defend their in-group against any potential threats.

Building off Turner et al.'s belief, previous studies have demonstrated that an individual's in-group identification and their way of self-categorizing themselves, although psychologically important to them, can prove to have negative social consequences. The way that people identify with a group and how they self-categorize this identity as an aspect of themselves, lays the foundation for their group-based appraisals of different events. With the group appraisal of other social groups or events, comes the generated group-level emotions, causing in-group-related actions and behavior tendencies (Mackie & Smith, 2016). These tendencies can be small, such as being a supporter of the group, or big, such as making sacrifices for the group by being the one to run all the errands for the group. Because of this, emotions tend to play a powerful role in driving actions that are beneficial or relevant to the in-group. According to Mackie, Devos, & Smith's (2000, as cited in Goldenberg et al, 2014) intergroup emotions theory, people can experience emotions like anger, fear, or guilt due to exposure to events relevant to their group. In other words, even sharing negative group-based emotions with in-group members could result in an increase in one's in-group affiliation, despite there being positive group-based emotion methods that encourage performance (Mackie & Smith, 2020).

Emotions play such an important role in how members respond to in-group situations and the way they behave since they control people's judgements and behaviors, in order to help avoid danger and ultimately attain goals (Mackie, Seger, & Smith, 2007). For example, a link has been found between positive emotions, increased sociability, and cooperation in groups (Isen, 1987, as cited in Lovaglia & Houser, 1996). It also has been proposed that negative emotions increase the psychological distance between people whereas positive emotions strengthen the relationships people have with others (Lovaglia & Houser, 1996). Similarly, Kemper (1984, as cited in Lovaglia & Houser, 1996) theorized that positive emotions such as happiness, love, and satisfaction are integrated together: positive emotions encourage behaviors that bind groups together. On the other hand, Kemper also theorized that negative emotions such as resentment, anger, or fear differentiate: negative emotions encourage behaviors that increase the differences amongst group members.

Previous studies investigating the relationship between emotions and group involvement and leadership, reported that those with high-status roles in groups (i.e. leadership role) reported more positive emotions than did other group members (Lovaglia & Houser, 1996). Astin (1999, as cited in Foreman & Retallick, 2016) built upon this research with his theory of involvement, suggesting that the quality of the student experience and the amount of time involved in the activity are both important factors in emotion and group-involvement effects. As observed by Pascarella and Terrenzini (1991, as cited in Foreman & Retallick, 2016), the amount of time and quality of student participation in school activities was positively linked to enhanced self-confidence, increased interpersonal and leadership skills, and high educational goals. Serving a leadership role was found to have an effect on both the quality and quantity of participation in extracurricular activities. As a result, students' decision-making capabilities increased, displaying higher levels of cultural participation, life management, and educational involvement (Foubert & Urbanski, 2006). Students who held leadership positions were also more likely to have a concern and empathy for others, an understanding of group issues and community history, a feeling of empowerment to implement changes, and the capability to build teams (Foreman & Retallick, 2016). Not many studies have focused on investigating the relationship between bad quality or quantity of participation, or the relationship between negative emotions/attitudes being expressed to members of groups.

The present study will examine the interaction effect of imagining a scenario that makes a group member feel supported or conflicted, and whether holding a leadership position or not has an effect on group-based emotions and group-supportive behavior. The methods and rationale in this study extend upon the previous research in this field of study. We decided to create different scenarios based on differing group-memberships teams, clubs, and organizations and examine the overall effects. We hypothesized that those who are in the Leadership & Support condition will show the strongest positive emotions toward their group and highest levels of group-supportive behavior. Alternatively, we hypothesized that those in the Non-Leadership & Conflict condition will show the least positive emotions toward their group and the lowest group-supportive behavior. Lastly, we hypothesized that those in the Leadership & Conflict condition will demonstrate weaker positive emotions but roughly equal levels of group-supportive behavior as the Leadership & Support condition.

Methods and Material

Participants

The study involved 168 college students (ages 18-25 years old) who were involved in clubs, organizations, or teams. Participants attended UC Santa Barbara (UCSB) and Oxnard College (OC), as well as other community colleges and 4-year universities. Participants were recruited through email listservs, social media (e.g., Snapchat, Instagram, etc.), and group messages.

Design

Our study is a 2 (Scenario: Support vs. Conflict) x 2 (Role: Leader vs. Non-leader) between-subjects design. We have two independent variables: scenario, with two levels (support vs. conflict); and role, with two levels (Leader vs. Non-leader). Both independent variables are manipulated and randomized. Our two dependent variables are feelings of positive emotion toward groups, and intended group-supportive behavior following manipulation. Both of our dependent variables are continuous and are coded using a seven-point Likert scale. We used a total of four experimental conditions that participants were randomly assigned to: (1) Support x Leader, (2) Support x Non-leader, (3) Conflict x Leader, and (4) Conflict x Non-leader condition. Our dependent variables of emotion and group-supportive behavior were presented as a pre-test prior to manipulation condition and as a post-test following manipulation.

Materials

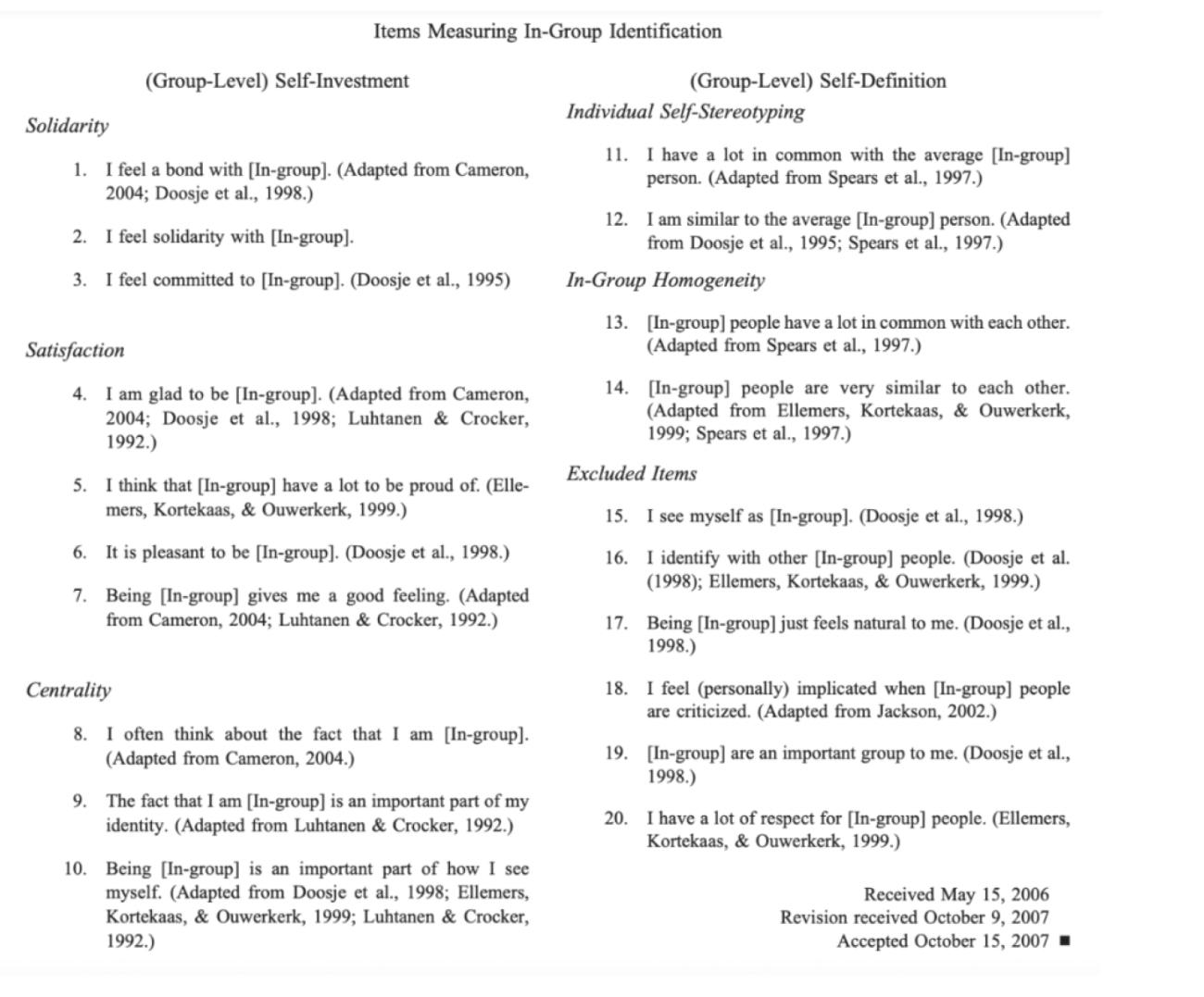

Using Qualtrics, we created a survey for participants to complete. To measure participants' emotions we used, and randomized, the Likert-scale questions in the following format (Mackie, 2020): rate the extent to which you feel (1) Proud, (2) Happy, (3) Admiring, (4) Angry, (5) Guilty, and (6) Anxious with a ranking of 1 coinciding with "strongly disagree," and 7 with "strongly agree." For data analysis purposes, negative emotions of anger, guilt, and anxiety were recorded as 1 being "strongly agree" and 7 being "strongly disagree." To measure participants' group-supportive behavior, participants were presented with the Leach et al. (2008) identification scale. We used three subscales (Solidarity, Centrality, and Self-Stereotype) instead of the five dimensions used for analyses of group identification (Table 1).

Procedure

Participants were presented with a consent form upon opening our Qualtrics survey via link or QR code. After signing the consent form, the participants were asked whether or not they were involved in any campus teams, clubs, or organizations. Participants who responded "no" to the campus involvement question were directed to the end of the survey and thanked for their time. Participants who responded "yes" were then prompted to select whether they belonged to a team, club, or organization. Participants were then asked to fill the pre-test questions with their group in mind. Following the pre-test, participants were randomized under one of four conditions: conflict-leadership role, supportive-leadership role, conflict-non-leadership role, and support-non-leadership role. Clubs and organizations were grouped and presented with the same Scenario x Role schema due to their similarities in duties, agendas, meetings, etc. The support condition instructed participants to imagine a scenario of feeling liked and accepted by their social group, while the conflict condition instructed participants to imagine a scenario of feeling neglected and disliked (more details in Appendix 1). In both scenarios, some participants were instructed to imagine they were a leader for their group and others were told to imagine they were general members. Following the scenario, participants were asked to fill out the post-test, asking them to indicate their emotions toward their group and levels of group-supportive behavior, with the scenario they read in mind.

Results

In our study, we were interested in examining whether an interaction effect would be observed on participant's emotions and group-supportive behavior by having participants imagine a support or conflict scenario in which they held a leadership position or were a general member. The data was analyzed using 2x2 (Support/Conflict x Leader/Non-leader) factorial ANOVA for each dependent variable. The data points of interest were the participant's emotional response, group-supportive behavior, and the effects of the interactions.

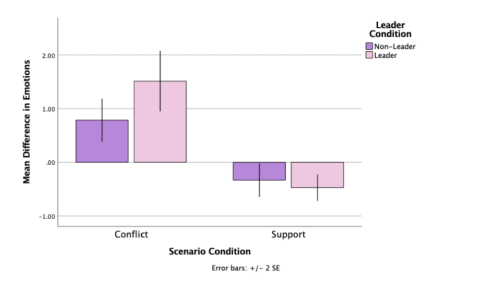

Our first prediction was that participants who were randomly assigned to the Leader x Support condition would show the strongest positive emotions toward their group and highest levels of group supportive behavior. After running our 2x2 ANOVA for emotion, we found a main effect of the type of scenario participants were given, F (1, 105) = 63.69, p < .001. The results indicated that participants who received the support scenario had the strongest positive emotions (M = -.405, SD = .753) compared to those who received the conflict scenario (M = 1.16, SD = 1.28). This data suggest that participants experienced positive emotions when in support scenarios with their group. There was no main effect of role, Leader vs. Non-leader, on participants' emotions, p > .05. There was however an interaction effect between scenario type and role in group, F(1, 105) = 4.9, p < .03. The results indicate that those who were randomly assigned to the Support x Leader condition did in fact report feeling more positive emotions about their group (seen in Figure 1), confirming part of our first hypothesis.

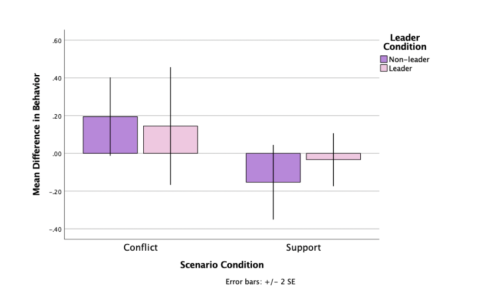

To determine whether the second part of our first hypothesis, that those assigned to the Leader x Support condition would also show the highest levels of group-supportive behavior, was supported, we conducted our second 2x2 ANOVA for group-supportive behaviors. The data indicates that there was a main effect of the support scenario found from group-supportive behavior, F(1, 103) = 5.89, p < .02. Additionally, there was no main effect found from the role, Leader vs. Non-leader, on participants' group-supportive behavior, p > .05. In other words, only the type of scenario had an effect on increasing or decreasing group-supportive behaviors, with support scenarios (M = -.090, SD = .450) yielding better group-supportive behaviors than conflict scenarios (M =.170, SD = .656). There was no significant interaction found between scenario and role from a participants' group-supportive behavior, p > .05. These results suggest that the second part of our hypothesis is not supported, since the difference in group-supportive behavior in the Leader x Support condition was not statistically significant (Figure 2).

Our second prediction was that participants who were randomly assigned to the Conflict x Non-leader condition would report the least positive emotions toward their group and show the lowest group-supportive behavior. As can be seen in Figure 1, those in the Conflict x Non-leader condition showed the least positive emotions compared to those in the Conflict x Leader condition. While group-supportive behavior decreased from those in the Non-leader condition, as seen in Figure 2, it also decreased for those in the Leader condition, and no significant difference was found between the two groups.

Our third prediction was that participants randomly assigned to the Conflict x Leader conditions would demonstrate weaker positive emotions but roughly equal levels of group-supportive behavior as the Support x Leader condition. Figure 1 demonstrates that those randomized in the Conflict x Leader condition experienced less positive emotions compared to those in the Support x Leader condition. Those in the Conflict x Leader condition were more likely to change their group-supportive behavior compared to those in the Support x Leader condition, and there was no significant difference between the two means (Figure 2).

Discussion

The results of our study supported part of each of our three hypotheses. First, as hypothesized, our results showed that participants who were placed in the Support and Leader condition had the strongest positive emotions toward their group. Contrary to part of our hypothesis, however, those in this group did not have the greatest effect in group-supportive behavior as predicted. Consistent with previous research by Lovaglia & Houser (1996), our study supports the notion that positive emotions strengthen the relationships people have with others, and negative emotions increase the psychological distance between people. This implies teams, clubs, organizations, and other social groups need to build a supportive environment to foster healthy and strong relationships between members. Not only will this sense of support positively impact those who are leading the groups, but it positively impacts general members.

Secondly, as hypothesized, our results showed that participants placed in the Conflict and Non-leader condition resulted in lower group-supportive behavior. Contrary to our hypothesis, the biggest change in positive emotions was seen in the Support and Leader condition. This result adds on to previous research by Mackie & Smith (2020), stating if other group members are not being supportive and instead creating a negative or hostile environment, the less an individual is going to be able to identify as a group member and foster a sense of belonging. This implies that groups with conflict or who lack effort to connect with their group, will result in many members having low group-supportive behavior, as they do not self-identify with the group.

Lastly, as hypothesized, our results showed that participants in the Conflict and Leader condition demonstrated to have weaker positive emotions compared to those in the Support and Leader condition. But on the contrary, those in the Conflict and Leader condition showed to have less levels of group-supportive behavior compared to those in the Support and Leader condition. This implies that when leaders are faced with conflicting situations, they are more likely to withdraw group-supportive behavior. This finding supports Kemper's (1984, as cited in Lovaglia & Houser, 1996) belief that experiencing negative emotions such as resentment, anger, or fear are differentiating and encouraging behaviors that will increase the differences among group members. This makes sense if we consider that leaders of groups typically carry more responsibility and stress; therefore, when conflicting situations arise, they may be impacted most negatively due to the time, planning, and effort they put into events with no turn outs. The leader may become less likely to offer their house as the gathering spot for a future event due to the conflicting emotions of people not showing up.

It is important to make note that there are a few limitations to our study. First, our study lacks external validity due to our small sample size. Because we have four conditions in our study, it makes it difficult to generalize our findings as after data cleaning, there were approximately 26-30 participants per condition. Another limitation of our study is that we did not provide a manipulation check for our conditions; therefore, we did not remove any responses that might have failed the check and affected our results.. Because of this, our internal validity is threatened as well as our external validity, the power of our statistical analysis, = 0.05, loses some of its statistical significance.

Further studies could be built upon this work by expanding the population beyond California, further along the coast. This may have an interesting impact: not only would there be a broader variety of responses, but we could observe the possible relationship/influences of weather in different areas. Additionally, we would suggest writing new scenario conditions that may better elicit positive and/or negative emotions and check for manipulation. This could prove to be interesting as our scenarios may not have been documented sufficiently or were relatable to participants' chosen group affiliation, thus not yielding any significant results.

The findings of this study are important to consider. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, people were attempting to resume pre-Covid lifestyles of socialization and connectedness. One of the easiest ways to form these connections is through joining teams, clubs, organizations, volunteer work, and so forth. Individuals who are aware and knowledgeable create a supportive environment for their group. Whether one is a leader or not, the above encourages others to feel connected, a sense of belonging, and to self-identify with their group, and it is associated with enhanced self-confidence, motivation, and increased interpersonal and leadership skills.

References

Foreman, E. A., & Retallick, M. S. (2016). The effect of undergraduate extracurricular involvement and leadership activities on community values of the social change model. Nacta, 60(1), pp. 86-92.

Foubert, J. D., & Urbanski, L. A. (2006). Effects of involvement in clubs and organizations on the psychosocial development of first-year and senior college students. NASPA, 43(1), pp. 166-182.

Goldenberg, A., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. (2014). How group-based emotions are shaped by collective emotions: Evidence for emotional transfer and emotional burden. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), p. 581.

Leach, C. W., Van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., ... & Spears, R. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), p. 144.

Lovaglia, M. J., & Houser, J. A. (1996). Emotional reactions and status in groups. American Sociological Review, pp. 867-883.

Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2016). Group-level emotions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, pp. 15-19.

Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2020). Group-based emotions over time: dynamics of experience and regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(7), pp. 1135-1151.

Smith, E. R., Seger, C. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2007). Can emotions be truly group level? Evidence regarding four conceptual criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), p. 431.

Appendix A

Team

Support Scenario

Leadership: Imagine that you are the team captain and plan a potluck for your team. The day finally comes and every single teammate shows up and has a great time bonding with each other.

Non-leadership: Imagine that your team captain plans a potluck for your team. You are offered to carpool with some other teammates and have a great time bonding with them and others at the potluck.

Conflict Scenario

Leadership: Imagine that you are the team captain and plan a potluck for your team. However, when the day finally comes, only a couple people show up, and you find out that there is another activity happening at the same time that no one told you about.

Non-leadership: Imagine that your team captain plans a potluck for your team and your teammates plan rides to get there. After finding out that no one thought of you and included you in their car, your only option is to drive to the potluck by yourself.

Club/Organization

Support Scenario

Leadership: Imagine that you took on a leadership role in helping to plan an event for your club/organization. Everything goes well, and everyone compliments you on how much they enjoyed the event.

Non-leadership: Imagine that you are part of the planning committee in helping to plan an event for your club/organization. Everything goes well, and everyone compliments your committee on how much they enjoyed the event.

Conflict Scenario

Leadership: Imagine that you took on a leadership role in helping to plan an event for your club/organization. Everything seems to be going well until you hear that some members of the club/organization don't really like your idea and are considering doing something else for the event.

Non-leadership: Imagine that you are part of the planning committee in helping to plan an event for your club/organization. Everything seems to be going well until you hear that some other members of the club/organization don't really like the committee's idea and are considering doing something else for the event.