Introduction

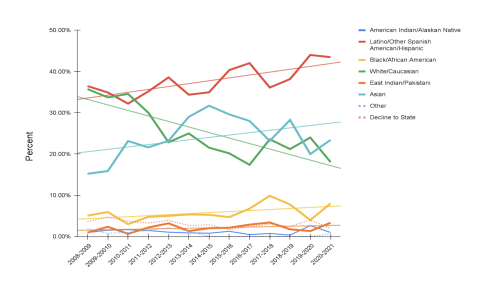

Many students find college to be a difficult adjustment from high school. Transitioning is especially difficult for first-generation, low-income students. Between 2008-2021, 3,408 undergraduate students were dismissed from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). Previous studies had found that racial and ethnic group membership, socioeconomic status (SES), and a variety of other social identities all play important roles in Latinx and other marginalized college students’ college experiences and well-being (Castillo-Lavergne et al., 2019). In our study, data collection and comparative analysis identified factors such as ethnic and socioeconomic identity that are associated with an increased rate of dismissal in college students. According to the demographics of dismissed students, the group of students impacted were Chicano/Latin/other Spanish, White/Caucasian, and Asian/Pacific Islander, in this order. For the majority of the students impacted, difficulties began in the fall quarter of their first year which resulted in a higher number of students being placed on probation in the winter quarter. First-generation and low-income students are identified in the group of dismissed students when socioeconomic variables are taken into account. It is critical to identify the reasons why students are struggling in their academic careers and being academically dismissed. Identifying these factors and taking action can help prevent these negative outcomes.Within this study, a survey collected specific details of those who were academically dismissed to identify who was being dismissed and why. According to the 42 survey responses, mental health appeared to play a huge role in the increased rate of college student dismissals. Following mental health affairs, the change in environment due to the Coronavirus-19 pandemic impacted many students. In addition, feeling lost and unmotivated also played a role.

Methods

Survey Test

A list of all the academically disqualified students was provided to us, along with their basic contact information (name, phone number, email, major, and year of dismissal). To identify the factors contributing to the increased rate of dismissal in UCSB students, these students were contacted for a survey review designed by other students who themselves had been dismissed from UCSB and thus empathize with the difficulties faced by many during the course of their academic careers. The researchers felt that adding a qualitative component to this study was crucial in understanding the unique experiences of each student. The students were asked questions such as:

- What is your hometown?

- How do you identify racially, ethnically, and nationally?

- What academic quarters did you attend at UCSB?

- When did your difficulties begin while attending UCSB?

- What was your age when you were facing academic disqualification, and what quarter was this?

- If you were to be approached by the university when you were facing difficulties, how would you have liked to have been approached?

- What would you have liked to see from the university in terms of assistance during your academic struggles?

- What were some ways you could have performed better as a student?

- If you could share insight for future students, what would it be?

- Please list any thoughts that you wish to convey that may not be covered in the questions above.

These questions allowed us to collect data on the 42 students who filled out the survey. The data were analyzed using Excel and displayed as pie charts, histograms, and bar charts to provide an array of visualizations. The analysis of the questions assessed who was disqualified, when, and why.

Based on survey responses, the groups affected were identified and quantified using a pie chart that showed the percentages of the ethnic identities dismissed. A bar graph was used to show a timeline of when the students began to struggle and which particular quarter they had difficulties with.

Results

Quantitative

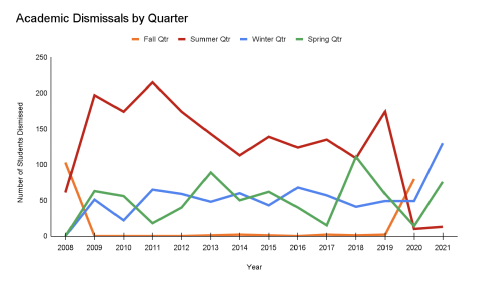

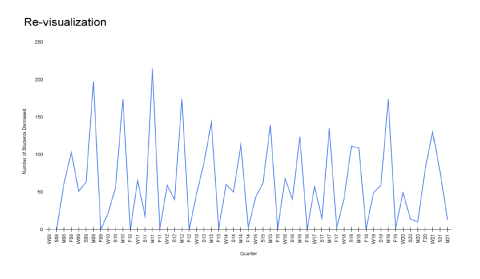

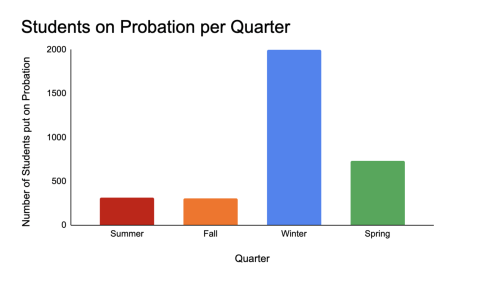

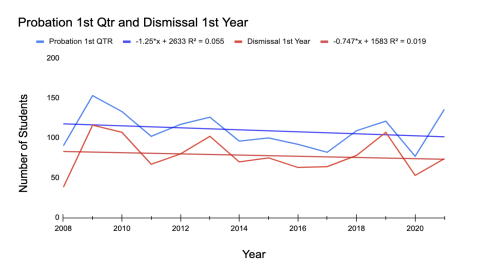

Between 2008 and 2021, 3,408 students were academically dismissed from UC Santa Barbara. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the dismissal trends by quarter between 2008 and 2021. We can see that there are little to no academically dismissed students during the fall quarter, which is reasonable considering that the fall quarter is the first quarter of the school year. Both the winter and spring quarters had a similar number of students who were dismissed. Being dismissed in the winter quarter means that the problems began in the previous fall quarter. Similarly, being dismissed in the spring quarter implies that the problems began in the previous winter quarter. Additionally, there is a large increase of students who were academically dismissed during summer quarter. Figure 2 provides another perspective for the dismissal rate by quarter; we can see that most academically disqualified students are dismissed in the spring quarter. This is important to note because although dismissal rates spike toward the end of the academic year, these students' academic struggles may begin as soon as they arrive on campus in the fall. The data reflects that the higher rates of dismissal in the years 2008 and 2020 may be strongly associated with greater world crises such as the stock market crash in 2008 and the Coronavirus-19 pandemic in 2020, suggesting that world events may have had a great impact on students' progress.

Kouyoumdjian)

dismissed (created by Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

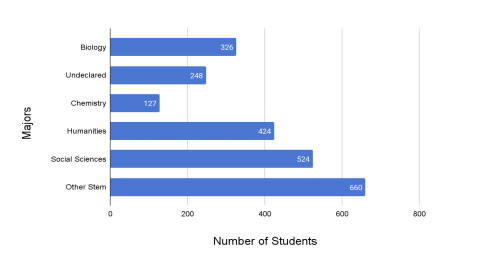

Within this study, we also investigated what majors were being academically dismissed and at what rates. The majors specified in the graph represented those in the pre-major and declared major. When the majors were analyzed using the study data, it was discovered that "Other STEM" majors dominate the dismissals, as shown in Figure 3. "Other STEM" represented the following majors: Environmental Studies, Mathematics, Actuarial Science, Mechanical Engineering, Computer Science, Physics, Geology, Computer Engineering, Psychology and Brain Sciences, Statistical Sciences, Aquatic Biology, Electrical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Ecology, Behavior, and Evolution.

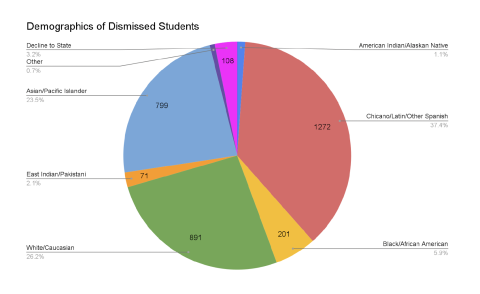

In terms of self-identified student demographics, it was found that of those students dismissed, 37.4% were Chicanx/Latinx/Other Spanish students, 26.2% were White/Caucasian, 23.5% were Asian/Pacific Islander, 5.9% were Black/African American, 2.1% were East Indian/Pakistani, 1.1% were American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 0.7% were identified as "other." This is illustrated on the pie chart in Figure 4 and in the re-visualization in Figure 5.

Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

(created by Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

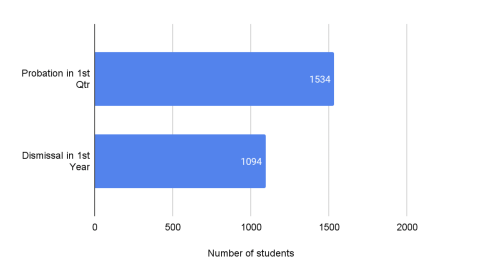

Figure 6 shows that due to first quarter grades, 98.89% of all first-quarter probations occurred in the winter quarter. In other words, the first-quarter grades determined the outcome of students on probation in their second-quarter (winter quarter). Our data revealed that 71.31% of the students with first-quarter probation were dismissed later that academic year. This finding importantly highlights that a significant amount of students that struggle academically in their first quarter continue to struggle throughout the rest of the year and even through future years. One student who responded to the survey wrote, word for word: "My difficulties began during my fall quarter of my freshman year. After that quarter I didn't have any difficulties until the winter quarter of my junior year and the winter quarter of my senior year." Figure 7 demonstrates that a significant number of students were put on academic probation during their winter quarter, again suggesting that students especially struggled during their first year and first quarter. Additionally, Figure 8 portrays the ongoing struggle over time, implying that this is a concern that exists and continues.

Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

(created by Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

by Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

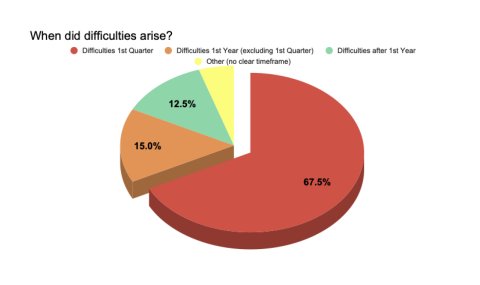

In terms of the student survey, 40 of the 42 students who completed the survey shared when their academic difficulties began. In addition to the data above, we found that 67.5% of the survey responses stated that their difficulties arose during the first quarter of their first year (Figure 9). There was 15.0% who said their difficulties arose during their first year, excluding the first quarter. This suggests that the difficulties incoming students face are associated with the struggle of adjusting to a new environment or to the quarter system. In addition, 12.5% of the students in the survey began having difficulties after their first year in college. This is where we can acknowledge that there are still certain circumstances and endeavors that students face at various points in their academic careers.

began for them (created by Matthew Kouyoumdjian)

Qualitative

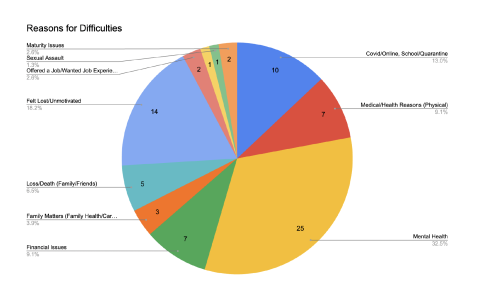

In addition to the quantitative results, we gave dismissed students the opportunity to share their experiences regarding the difficulties they faced and the obstacles they encountered while at UCSB. The following are a few of the many stories we gathered as data to determine what factors contributed to an increase in the rate of dismissal. The qualitative information was gathered in order to delve deeper into the students' specific opinion regarding their time here. From an analysis of their responses, a pie chart was created to categorize the reasons for their difficulties. These findings have allowed us to be more aware of the specific factors that impact student success such as mental health, COVID-19, struggles with time management and motivation, health issues, financial issues, and personal issues.

Student Responses. Aside from the student surveys, we emailed each student individually, giving them the opportunity to discuss the difficulties that led them to their academic dismissal. The first two responses highlight that academic dismissal was mainly attributed to the ongoing global crisis caused by the Coronavirus-19 pandemic and the shift to online learning. These factors had a significant impact on students' mental health and motivation to continue their studies. Two students shared:

The Covid pandemic took a serious toll on my mental well being especially when I was already struggling previously with time management while having a job and navigating my freshman year of college. I struggled a lot with my chemistry class which led to paying less attention to other classes and unfortunately created a domino effect of not doing well academically. Once the pandemic hit and we had to return home I did not adjust well to online learning and my motivation and mental health went downhill fast. Even after taking summer school classes I was not performing well. This period of time was very difficult for me as education has always been a passion of mine and graduating from college as a first generation student was and still is a part of my dream for my future and I have every intention of achieving this goal.

Unfortunately like many others my final quarters were synchronized with the spread of Covid. I had already been lagging in motivation by that point, the stress of the pandemic was simply the straw that broke the camel's back and I found myself unwilling to leap the last hurdle. After working in the outside world for a while now I have come to realize the value of the education I failed to conclude and I am eager to return to do so in any way I can.

Other challenges students face are health-related issues and mental health-related issues, as shown in the next few responses from students. Five students stated:

I was disqualified when my grades dropped mostly because of health related issues. I underwent surgery the first week of Winter 2020. I wasn't able to attend class for almost half of the quarter and I failed a couple classes. Spring quarter 2020, I tried bringing my grades up but wasn't prepared for the challenges of online classes. That same quarter the transition to quarantine severely impacted my mental health to the point that it affected my academics.

I struggled with some major illnesses and mental health/anxiety issues but I am doing everything I can to get back on track and graduate because I have a Commercial Real Estate job lined up but I need my degree first.

Overall, my initial academic disqualification had due to with more internal issues: I lacked control, or, I lacked the desire to control myself perhaps, I was overconfident in my abilities and I didn't put in nearly as much work as I know I can or should and a few more personal matters all led to me being initially disqualified.

My first two years at UCSB felt like I was constantly struggling to survive. Instead of being able to focus on being a student, I was spreading myself thin and over exerted myself to try and keep my mind occupied and keep away any anxious thoughts about my instability. I'm interested in the Student Retention Program because I want to take advantage of resources on campus in a way that propels me toward finishing my education. My current transcripts reflect a student who was struggling not only academically, but financially, emotionally, and physically. I have worked really hard to control the latter, and I've given myself stable ground to grow on.

I've been wanting to return to continue my education and achieve my degree, but I have been dealing with depression the past couple of years. I left Santa Barbara because I was too stressed out trying to balance being a full time student with a full-time job, a part-time job and a dog while trying to save enough to pay $1500 in rent every month. I decided to become homeless and quit my jobs because I thought that would be easier for me, but it just made me feel even worse. Then I lost my dog in Santa Barbara, and I haven't been back since. It's hard being poor. I know getting a degree will help me get out of poverty. It's the only thing holding me back from pursuing a career in my field of interest. I want to do more with my life, like I use to. I want to help people again and give back to my community. I miss the person I was. I’ve been waiting for this and the timing couldn't have been any better.

Many students shared that financial difficulties became a main stressor in their academic careers and ultimately resulted in academic disqualification. Two students shared:

I had no idea I was disqualified. I’ve been having a lot of personal and financial issues but I was hoping to return to ucsb for spring quarter.

During that time I struggled a lot financially and was constantly trying to find work. I ultimately failed in balancing out school and work.. I saw it was getting difficult for me to keep up with classes and I decided to leave and return home so that I can realign priorities and save money instead of feeling like I was wasting time and money failing classes. Since then I took classes at community colleges on and off because of a consistent, busy work schedule. I have learned to balance out my schedule a bit more since I am now much more financially stable and I am looking to finish my undergraduate requirements as soon as possible.

Discussion

Many factors negatively alter these young adults’ mental health, including numerous academic, financial, and social stressors. Others were potentially caused by world events, such as the market crash in 2008 and the Coronavirus-19 pandemic in 2020. Students at UCSB responded with suggestions as to what the university could provide or change to better the academic environment. For example, there were plenty of responses concerning the academic advisors, more direct guidance, and more supportive department heads. One student reported, based on the survey responses on what students would have liked to see from the university in terms of assistance during their academic struggles, "Empathy for one, especially from advising (and ESPECIALLY bio advising)." There were also plenty of responses regarding Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS). Some responses expressed, "Better mental health counseling than CAPS," "Better mental health support and better check-ins with students who are struggling academically,” and "More accessibility to counseling and therapy in CAPS, especially to first-generation students and students who come in from low-income areas…." At UCSB, the students expressed a desire to expand the university’s tutoring resources and the availability of office hours.

The significance of our findings is that they suggest that ethnic and socioeconomic factors play an important role in students' college experiences. One major finding that emerged from this study is that although UCSB is a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), the students who are being academically dismissed at the highest rate self-identified as Chicanx/Latinx/other Spanish. It is important for the campus’s administrators, staff, and faculty to reflect and to understand this issue to meet the needs of their students. Additionally, mental health, motivation, health-related issues, and financial difficulties are at risk during individuals’ college periods, altering and impacting one’s academic success and overall well-being.

Limitations & Future Directions

Students not responding to the retention survey or simply declining to state their ethnicities are potential errors that prevent an accurate representation of the groups impacted by the diverse student population from 2008 to 2021. Furthermore, not going into detail about what majors were classified as "Other STEM" could potentially limit the analysis on who was being academically dismissed during these times. The purpose of this study was to identify the factors as to why students are being academically dismissed. These were specific to students from UC Santa Barbara; therefore, it is important for other schools to understand the challenges their own students face to appropriately address their needs and well being.

In addition, there was a previous study by Schwartz that focused on the development of skills and attitudes that would empower first-generation college students to use social capital and on-campus connections during the transitory stage to college, written by Schwartz et al. (2017). This past study tried to understand how the intervention may have influenced participants’ experiences during their first year in college, focusing on their attitudes and behaviors (Schwartz et al., 2017). It was said that such social capital practices, such as better support for students, closer connections with instructors, more resources to decrease help-seeking avoidances, can benefit and guide first-generation college students to succeed in college. The results suggested that their program can positively influence first-generation college students' attitudes and behaviors related to using their support from instructors to improve their academic performance (Schwartz et al., 2017). From Schwartz’s data, results showed that students in the intervention group who has access to more resources and office hours, had better relationships with instructors, increased engagement in help-recruiting behaviors, increased network orientation (belief in the usefulness of seeking support), and decreased help-seeking avoidance (Schwartz et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to identify the factors that contribute to students being academically dismissed. It is critical that schools understand their own students' reasons for struggles to improve each student's well-being and academic career. In the study, the data collected from the students' stories and the surveys demonstrate the ethnic and socioeconomic identifications that are correlated with an increased rate of dismissal among college students. Moreover, it showed that mental health plays a significant role in students' academic careers. Many students were impacted by mental health issues, a change in environment caused by the Coronavirus-19 pandemic, and feelings of being lost and unmotivated. Our findings are crucial because they highlight that ethnic and socioeconomic factors play an important role in students' college experiences. Furthermore, these factors put mental health at risk, triggering life-long consequences in academic careers and in real-world experiences. Students responded with ideas for what the university could provide or change to improve the academic environment; they ask for better training for academic advisors, so that students from diverse backgrounds and experiences receive better support. They ask for more mental health providers on campus or better access to the mental health providers. They also suggest better access to resources. It is crucial for schools to understand students' reasons for difficulties in order to improve each student’s well-being and academic careers. Listening to students' needs, being aware, and providing attentive care will be a great start in better supporting these students.

The findings of this study brings on several next steps that universities can take to improve their students' academic success and well-being. The next step after listening and being aware of students' needs, universities would need to take these recommendations seriously and enforce policies and programs to address the identified issues. Some ways to take action would be to invest in additional mental health services, offer additional training for academic advisors, and to take initiative to ensure that all students have access to resources that will help them succeed academically and personally.

References

Castillo‐Lavergne, C. M., & Destin, M. (2019). How the intersections of ethnic and socioeconomic identities are associated with well‐being during college. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), pp. 1116–1138. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12358

Mahmoud, J. S., Staten, R. T., Hall, L. A., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, Life Satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3), pp. 149–156. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.632708

Schwartz, S. E., Kanchewa, S. S., Rhodes, J. E., Gowdy, G., Stark, A. M., Horn, J. P., Parnes, M. K., & Spencer, R. (2017). “I'm having a little struggle with this, Can you help me out?”: Examining impacts and processes of a social capital intervention for first-generation college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(1-2), pp. 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp