Introduction

Low-income, first-generation (LIFG) college students have lower retention and graduation rates, typically having weaker connections to campus support as compared to more affluent, continuing generation students (Moschetti & Hudley, 2015). Although many of these LIFG students are provided the financial assistance necessary to get them through the door, they do not receive adequate resources on how to navigate the institution once on campus. Upon arrival, students in this demographic are typically unaware of how to navigate the institution, how to ask for help, or who to go to, which negatively affects their academic success (Bassett, 2023).

Through exploration of a successful model, we can understand why students of this demographic have certain educational outcomes and how they can then improve their upward mobility. The Promise Scholars Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara offers full financial aid and a wrap-around, high-touch model to LIFG students (UC Santa Barbara, 2025). Beyond funding, the wrap-around service includes holistic support and guidance, while the high-touch service functions as an invasive type of model where program administrators reach out directly to individual students. With this support system, the Promise Scholars have higher retention rates compared to their counterparts. With this in mind, the initial research question at hand is: what contributes to the success of LIFG college students when they are provided with wrap-around services?

My research contributes to broader sociological discussions about equity and access for LIFG students in higher education due to structural barriers. This study highlights how these students, often socialized to be independent, must unlearn this individualism to embrace new networks that promote their success in college. Programs that provide administrative and community support—through mentorship, empowerment, and transmission of both cultural and social capital—can aid in disrupting patterns of educational inequities.

Literature Review

Existing literature demonstrates that low-income, first-generation (LIFG) students have less access to and knowledge of resources for their transition into college, despite being among the students who require the most assistance. The studies analyzed in this section suggest that beyond the funding they receive to enter the university, LIFG college students benefit significantly from faculty guidance and community support, specifically on the basis of finding community and navigating the unfamiliar institution.

A study by Dr. Roxanne Venus Moschetti and Dr. Cynthia Hudley highlights how low-income, first-generation college students face disadvantages due to their lack of knowledge on important resources and networks to assist them in their transition into postsecondary education. Moschetti and Hudley (2015) found first-generation status to be the strongest predictor of whether students would leave university before their second year (p. 236). In addition, lower social class and first-generation status are identified as the most significant predictors of how much social capital that particular demographic has while in university. The study found that, although LIFG students need the most assistance during their transition into college, they struggle to locate the necessary resources, concluding that a development in social networks can assist these students to manage and navigate their new surroundings. On a similar note, multiple studies have found that educational institutions, administrations, and faculties can aid the academic trajectory and upward mobility of LIFG students through the transmission of cultural capital. Richards (2022) posits that cultural capital can be passed on to LIFG students by these educational institutions in the form of students’ help-seeking dispositions and specialized knowledge (p. 241).

Existing research attributes faculty and administrative support as an important factor in the success of LIFG students. Dr. Geneva Sarcedo (2022) identified that when LIFG college students of color have supportive faculty relationships, it positively impacts the student’s achievement and retention rates (p. 128). Dr. Becca Spindel Bassett (2023) corroborates this claim, suggesting faculty have a key role in making more structurally and culturally supportive colleges (p. 366). However, Bassett (2023) also claims that when compared to continuing-generation students, first-generation students are less likely to turn to faculty for support (p. 368).

A significant theme that previously mentioned studies did not cover was the importance of belonging and community in the higher educational trajectory of LIFG students. Dr. Darris R. Means and Dr. Kimberly B. Pyne (2017) conducted a qualitative case study to gauge first-year LIFG college students’ perceptions on their sense of belonging and institutional support. Unlike the other studies, they found that a student’s sense of belonging is among the most important aspects for academic success, resulting in retention, mental well-being, and academic achievement (Means & Pyne, 2017, p. 910). When students do not feel like they belong at an institution, they are more likely to leave the university, making the interactions with their support structures all the more valuable. LIFG students’ sense of belonging in relation to need-based scholarship programs is another important aspect underscored in this study. Means & Pyne (2017) found need-based scholarship programs to be highly effective for LIFG students, as they go beyond offering financial support, providing social and emotional support as well. In their study, one student regarded his scholarship program as “a large family” (Means & Pyne, 2017, p. 916). Corroborating the results of the other studies mentioned, Means & Pyne (2017) supports the finding that the attributed faculty of a scholarship program is an important variable in a student’s sense of belonging.

Evidently, the gravity of supportive faculty and administrative support for LIFG students is of great significance. Among the different ways faculty can support students, relatability is a powerful tool in building relationships with students. When faculty members share that they are also first-generation, and when they share personal anecdotes of previous struggles, this contributes to supportive relationships that promote students’ self-efficacy and advance their success (Sarcedo, 2022).

Methods

One portion of the qualitative data analyzed in this study is from interviews with the Promise Scholars Program founder, Mike Miller, and the current program director, Holly Roose. The purpose of these interviews was to gather firsthand understanding on how the wrap-around model functions and what institutional forces impact the barriers that underrepresented students in higher education encounter. Because the administrators were my interview subjects, I opted to contextualize my research prior to obtaining informed consent. The interviews took place on two separate dates in both administrators’ respective offices, spanning roughly 30 minutes. My interview guide consisted of five open-ended questions, as follows:

- What was your upbringing and your educational background?

- How was the Promise Scholars Program founded, and how did you get involved?

- What does your position consist of?

- Can you tell me about a particular instance where a student needed support from you?

- What is the most important aspect of this program?

Another point of qualitative data collection includes observations, which were conducted in the Promise Scholars office to gauge the environment of low-income, first-generation (LIFG) students who have access to wrap-around services. The office is situated on the second floor of the Student Resource Building next to the Educational Opportunity Program office, a program that provides resources to income-eligible, first-generation students. I sat in the office for two hours, observing and writing down the interactions between students entering the office. During that time frame, eight students were in the office, five of which were the main subjects of my observation. The type of observation method used in this study is effective due to the myriad of students who enter the office space daily, providing random samplings of subjects. Being that this study’s main intention is to gauge the effectiveness of the wrap-around services on a student’s academic success, the Promise Scholars office is the ideal space to find students who take advantage of the services offered.

I approached this qualitative data through thematic analysis, which aims to explore key themes and patterns that develop out of the data from the ground up, as grounded theory suggests (Charmaz, 2014). Thematic analysis is appropriate for my research because it allows for the experiences and social processes to be understood through the recurring themes, which is where the theory emerges. This is opposed to approaching the data with preconceived notions or theories. Similarly, this analysis draws on Charmaz’s (2014) grounded theory approach, where the initial qualitative data is collected to create a theory, since my final theoretical model did not emerge until all data was analyzed. Silverman’s (2005) approach on qualitative analysis is also prevalent in this study, where a specific qualitative analysis of data reflects larger social processes and systems. Similarly, an inductive coding strategy was used for this study, where codes and themes emerged directly from the data. This approach served to reduce preconceptions, allowing for new avenues of analysis to develop that may have otherwise not been considered, as Charmaz (2014) suggests.

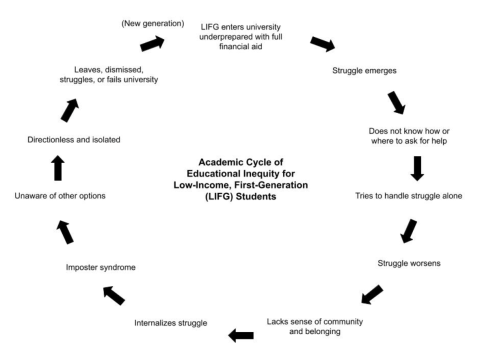

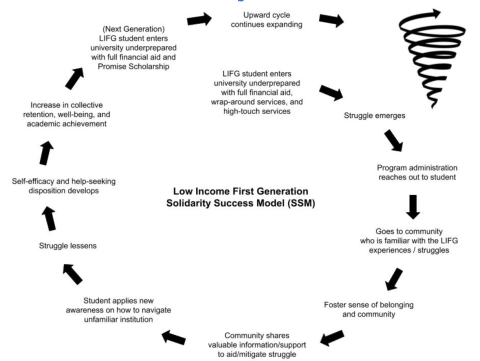

Lastly, through gathering data from the interviews, observations, and existing literature, I constructed two diagrams to visually represent the theoretical model that emerged from recurring themes and patterns. In regards to reflexivity, I come from a low-income, first generation, underrepresented background and am a recipient of the scholarship program explored in this study.

Interview Findings: Role of Faculty and Administration

A significant theme in the data is the role that faculty play in the success of low-income, first-generation (LIFG) college students, gathered through the interviews conducted with program founder Mike Miller and program director Holly Roose. Both interviewees acknowledged that higher educational institutions lack adequate support for LIFG students. Roose named her position as program director a “24/7” job, committing to empowering students through academic and personal mentorship. When asked what the most important aspect of the Promise Scholars Program is, she said, “The students. That’s it. That’s all I care about. I will literally, like, steamroll pretty much over everything that gets in my way if it’s gonna fuck up my kids’… ability to… move forward and graduate.”

When asked about the high-touch aspect of the program, she shared an example: when the academic quarter ends, she runs progress checks on all of her students. For the students who seem to be struggling academically, she reaches out to them personally to get a sense of their situation and to assess what they need. Typically, this would mean being set up on a time-management accountability system for the following quarter to ensure the student gets back on track. She noted that many science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) students fail their initial major-requirement courses in their first quarter, which takes an immense toll on their academic and personal well-being. She added, “There’s also that thing of, like, the pressure that they put on themselves—and culturally—to come in as a bio[logy] major because they think that’s the only option,” which encapsulates the pressures and expectations of first-generation, low-income, underrepresented minority students feel to pursue certain career paths due to cultural influences and a lack of knowledge concerning other career options.

A different recurring theme throughout the interview with Roose was the need to set students up for success starting at the beginning of college, especially when they come from underrepresented and underprepared backgrounds. In the following excerpt, she details a common experience for students from underrepresented backgrounds upon entry into the university: “We have these students that are coming into STEM majors, underprepared from underperforming high schools, and [the institution is] not providing them with the preparatory materials that they need to do all those majors, and so that’s where we’re really failing them. Because once we admit the students, it’s our responsibility to graduate them. But the school doesn’t see it that way. The school sees it like, Oh well, good luck, you don’t belong here, then. You know? That’s how the faculty see it.” She describes a pattern where students from these underrepresented, underprepared backgrounds are admitted into a prestigious institution with financial support, but they are left directionless upon arrival in terms of how to succeed.

The significance of developing help-seeking dispositions alongside community support emerged as an additional theme. Miller emphasized that beyond providing LIFG students with full tuition funding, an important factor is “making sure students feel comfortable asking for help.” When asked about the most important aspect of the program, he answered with, “the community that is built. You know? Not just the community within our scholars, but within staff and faculty. When faculty find out that you’re a Promise Scholar, that means something on this campus … It’s like the old saying: ‘it takes a village to raise a child,’ and I think it takes a village to really educate and support our most vulnerable students.”

Lastly, a pattern extracted from the data is the similarities in background both interviewees have with the Promise Scholars demographics, both coming from LIFG upbringings. Miller, who grew up on a Native reservation in Washington, shared that both of his parents struggled. His father was incarcerated for the majority of Miller’s life while his mother was addicted to hard drugs. Similarly, Roose was raised in a poor Black community in Alabama and grew up in a “tumultuous household” with “a lot of violence.” Both Miller and Roose reflected on their high school experiences. Miller graduated with a 2.1 GPA; Roose graduated with a 1.9 GPA. Notably, Roose keeps a copy of her transcript up on the wall in the Promise Scholars office to show her students where she comes from.

Observation Findings: Promise Scholars Office

The Promise Scholars office at the University of California, Santa Barbara was originally a very small office in the Financial Aid building that could fit about seven people. According to Holly Roose, program director and selector of scholars for the program, it has expanded from 124 students in 2015 to 1,224 in 2024, and they were granted the larger space during the 2024-2025 school year. Now situated in the Educational Opportunity Program suite, the Promise Scholars office is roughly ten times larger than the former one, allowing for more students to enter and occupy the space. In the office, students have access to the two program directors. Additionally, there are multiple tables and seats for lounging and studying, as well as fidget toys, puzzles, coloring books, and an assortment of snacks. Once a week, a therapy dog is brought into the office for the students to destress with.

During the observation, I sat in a chair near a table of students and the program director’s (Holly Roose) desk. There were eight students in the office, all of whom were students of color. Five of the students sat at one table. Conversations revolved around academic support, with three of them discussing readings from their respective classes. One student was unable to find a book they needed at an affordable price, and the student next to her showed her an online database with free access to books. They were very informal, cracking jokes, laughing together, and, at one point, breaking out into song.

“I need to plan my schedule for next quarter,” another student expressed. The rest then discussed “pass time” dates, referring to the allotted time slot for students to select their courses for the following term. Immediately after, the same student voiced how “stressed” she had been recently and how it was “affecting [her] eating habits.” A different student brought up nutritionist services offered on campus. The first student asked, “There’s a nutritionist on campus? Where?” to which her peer responded, “The Student Health Center.”

A different student announced to the room, “I went to my department advisor; they were useless,” to which the assistant program director responded by asking what major. “Political science,” the student responded, “They just told me how many classes to take, but they didn’t tell me what.” The assistant program director replied, “As a former academic advisor for the College of Letters and Science, they are not allowed to tell you what classes to take.” A few minutes later, the student returned to the subject, asking the assistant program director, “Can you help me pick out classes?” and the assistant program director immediately went over to the student to assist them.

Discussion

The qualitative data analyzed in this section is from interviews with the Promise Scholars program founder Mike Miller and program director Holly Roose alongside field notes from observations conducted in the program office. The data focuses on how the relationships low-income, first-generation students have with their community (involving both faculty and peers) influence their trajectory in college and overall upward mobility both individually and collectively.

Key Themes and Patterns

Significant themes from the data are community, relatability, and belonging, which underscore how the presence of social support from peers and faculty alike has a key role in promoting the academic and personal success for low-income, first-generation (LIFG) college students.

In my observations of the Promise Scholars office, the students present at the time displayed a strong sense of community and assistance. For example, the student who voiced how her stress was affecting her eating habits was recommended by a peer to utilize the campus nutritionist services at the campus Student Health Service, which the other student was initially unaware of. The interaction points to help-seeking dispositions that emerge when LIFG students have a community familiar with their struggles and how to handle them.

The theme of relatability and belonging is exemplified with the role of faculty. Both faculty members also emphasized that LIFG students need to feel like they belong in higher educational institutions. Holly Roose and Mike Miller both shared that they come from tumultuous, LIFG backgrounds. In the Promise Scholars office, Roose even keeps her high school transcript with low grades and GPA on display. When being mentored by these successful faculty members who are transparent about their struggles, LIFG students are shown that they can be successful in the face of adversity. There is trust that is built between the faculty and students who relate to one another’s experiences, which ultimately strengthens their sense of belonging.

From this data analysis, I developed the Low Income First Generation Solidarity Success Model (SSM), which illustrates how the perpetual cycles of educational inequity among LIFG students can be broken when they have a community that they can deeply resonate with. Drawing on observations from the Promise Scholars program, the SSM posits that when the institution fails to provide adequate support for LIFG students, these students can thrive by relying on one another for mutual support as well as resource acquisition and distribution by learning help-seeking dispositions.

The first diagram depicts the Academic Cycle of Educational Inequity for LIFG students. In this diagram, the typical trajectory of LIFG college students is shown as a perpetual cycle in which the student enters the institution and handles their struggles on their own with no support system. This cycle continues with each new generation of LIFG students that enter the institution.

Rather than the perpetual cycle of educational inequity through an individualist approach, the SSM functions as an upward spiral that funnels outward as the solidarity within the LIFG community strengthens generation after generation. As the spiral expands, so does the collective mobility of the demographic, which contributes to systemic changes in education and beyond.

The SSM model also draws on existing research on the topic of LIFG student success. Means & Pyne (2017) focus on how belonging is one of most important factors in achievement, retention, and well-being among LIFG students (p. 910). Similar to my research, this study highlighted need-based scholarship programs as powerful sites for fostering belonging for LIFG students, going beyond the financial aspect that the support system provided. The study also noted that faculty are one of the most significant variables in fostering a sense of belonging (Means & Pyne, 2017). Through my findings corroborated by existing literature, the SSM contributes to a broader sociological discussion on methods to heal structural inequalities faced by underprivileged communities. By analyzing the Promise Scholars Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara, there is insight on a wrap-around, high-touch model that functions effectively, given that these students have some of the highest retention and graduation rates across all demographics at the university. According to Roose, the Promise Scholars Program’s LIFG four-year graduation rate is at a 70% completion rate, compared to only 61% (Data provided by UC Santa Barbara Office of Budget and Planning) of the same demographic campus-wide. The SSM shows how individual success and collective upward mobility within a system that is not catered to LIFG students can be achieved through an empathetic, collectivist lens. Rather than feeling isolated and unsupported by the institution that does not support them, LIFG students have turned to those who they can most relate to for support in both belonging and resource acquisition,dismantling wider, systemic barriers in the process. As such, the Promise Scholars Program proves to be an effective model that creates success for LIFG students, serving as a force that shows breaking patterns of generational poverty.

Limitations of this study have to do with the small sample size of interviewees and field observations. Given the size of the program, it is not possible to view the interactions between all of the Promise Scholars Program cohort. Additionally, this study lacks a comparison to an existing model that is ineffective, such as LIFG students without access to wrap-around services. In a more expanded version of the study, I could make this comparison.

Conclusion

Throughout this study, I have highlighted the importance of community-based support systems that can aid in dismantling barriers for low-income, first-generation (LIFG) college students. Providing financial aid for this demographic does not suffice for the success of their academic trajectory. Beyond admission and financial support, it is necessary for these students to accumulate social and cultural capital in order to navigate the institution. The Promise Scholars Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara shows that a wrap-around, high-touch model works to foster help-seeking dispositions, to promote belonging, and to improve retention and graduation rates for LIFG students.

Through interviews with the Promise Scholars Program administrators and field observations of the Promise Scholars Program office space, my research shows that faculty support, community, and relatability are positively correlated with making up for inherent educational inequities. Based on my research, I created the Low-Income First-Generation Solidarity Success Model (SSM), which calls on a collectivist approach to strengthen both individual and group upward mobility, because the experiences of LIFG students should not be a journey of isolation but one of solidarity.

Higher education institutions are responsible for promoting models of wrap-around, community-based interventions in order to close gaps of educational disparities. Through investment—of money, time, and people—in programs that support LIFG students beyond financial aid, this demographic can thrive in the pursuit of a better future that generations before them did not have.

References

Bassett, B. S. (2023). “Do You Know How to Ask for an Incomplete?” Reconceptualizing Low-Income, First-Generation Student Success Through a Resource Acquisition Lens. Harvard Educational Review, 93(3), 366–390. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-93.3.366

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications.

Means, D. R., & Pyne, K. B. (2017). Finding My Way: Perceptions of Institutional Support and Belonging in Low-Income, First-Generation, First-Year College Students. Journal of College Student Development, 58(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0071

Moschetti, R. V., & Hudley, C. (2014). Social Capital and Academic Motivation Among First-Generation Community College Students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2013.819304

University of California, Santa Barbara. (2025). About. Promise Scholars Program. https://promisescholars.sa.ucsb.edu/about

Richards, B. N. (2020). Help-Seeking Behaviors as Cultural Capital: Cultural Guides and the Transition from High School to College among Low-Income First Generation Students. Social Problems, 69(1), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa023

Sarcedo, G. L. (2022). Using Narrative Inquiry to Understand Faculty Supporting First-Generation, Low-Income College Students of Color. Journal of First-Generation Student Success, 2(3), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/26906015.2022.2086087

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.