Introduction

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that more than half of Americans will be affected by psychiatric illness at some point in their lives (CDC, 2023). On average, patients do not receive an assessment until a year after symptoms first arise (Johannessen et al., 2001) because there is so much stigma surrounding mental health care services. The effect of this stigma is particularly significant for Latinx communities, a population which has become the largest ethnic minority population in the United States. Latinos are less likely to receive treatment for psychiatric illness, and when they do seek out help, their treatment retention rates are much lower than their white counterparts (Kataoka et al., 2002; Merikangas et al., 2010). These alarming statistics tell a complex story of injustice, and the patients themselves are not to blame.

According to the CDC, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) affects almost 6% of the population worldwide, not including people who go undiagnosed (CDC, 2022). Contrary to popular belief, this disorder is much more complex and nuanced than the stereotypical depictions of children who cannot sit still in class; individuals with ADHD can demonstrate symptoms that are hyperactive, inattentive, or a combination of the two (APA, 2013). ADHD has a range of effects on attention, emotional regulation, and overall cognitive functioning. It is a multifaceted disorder that changes the way an individual learns and interacts with the world around them. Populations who are underdiagnosed may face further challenges. For example, women are less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, as their symptoms tend to be much more internalized (CDC, 2022; Gershon & Gershon, 2002). This results in the underdiagnosis of women with primarily inattentive symptoms, which leaves them vulnerable to developing comorbid disorders like depression and anxiety (Gershon & Gershon, 2002). Because clinical psychology research has a long history of excluding Latinx populations, especially those with neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD, Chicanx/Latinx women face an intersectional lack of support not only because of their gender identity but also because of their ethnicity. This lack of perspective in clinical research has left women of color out of the conversation, which has direct implications for treatment interventions.

Enculturation and Stigma

Latinx individuals are at high risk for developing symptoms of anxiety and depression (Zvolensky et al., 2021), and the population as a whole is both likely to develop severe psychiatric illness and unlikely to receive the support they need from mental health care services. Their reluctance to utilize mental health care services may be explained in part by the connections between acculturation, enculturation, and stigma within the Latinx community (Villatoro et al., 2014). "Acculturation" is defined as Latinx individuals' assimilation to the dominant American values, whereas “enculturation” is defined as those individuals’ focus on following traditional Latinx values and customs (Hirai et al., 2015). Hirai has found that Chicanx individuals with higher levels of enculturation are more likely to prefer culturally relevant or religious methods of treatment over traditional therapy. "Collectivism" is an enculturated value within Latinx culture that manifests as a strong emphasis on making decisions as a family, supporting one another, and honoring elders. Villantro calls this cultural phenomenon "familismo," which can range from high to low levels of family support. From a clinical perspective, familismo is associated with varying degrees of "perceived family support" that can affect the patient's decision to seek out treatment (Villantro, 2014, p. 357). If, for example, an elder in the family isn’t supportive of the patient, they will feel as if it would be disrespectful to continue with treatment. This may be misinterpreted as the patient choosing to not receive the care they need, but in reality this issue is more multifaceted. Latinx patients often turn to other options because the mental health care system fails to provide them with treatment that respects their cultural values—such as familismo—and overall culturally responsive care.

ADHD in Latinx Populations

Latinx individuals are a marginalized group that is underserved by the mental health care system. The factors contributing to the lack of support for this population are complex. Latinx patients demonstrate more unmet mental health care needs in comparison to their white counterparts (Lawton et al., 2014). Lawton uncovered that traditionalism influences Latinx parental beliefs on ADHD, which can potentially affect help-seeking behavior. Traditionalism in this context is the act of adhering to typical Mexican values, such as familismo, Catholicism, and strict gender roles. Religious views pertaining to Catholicism are especially impactful on reluctance to seek help from mental health care services, as Latinx individuals are encouraged to priortize religious support (Lawton et al., 2014). More importantly, Latinx families who are enculturated may be opposed to receiving support from providers whose cultural values differ from their own (Lawton et al., 2014). Another study focusing on Dominican mothers’ relationships with their ADHD-diagnosed children identified that "verguenza" (embarrassment) is a contributing factor to low treatment retention rates (Arcia et al., 2002). Verguenza is rooted in shame, which manifests when mothers are accused of being a bad parent when their children misbehave. For these Dominican mothers, there is a strong negative stigma associated with the way ADHD affects children’s behavior, which could potentially be consistent within other Latinx subpopulations as well. However, researchers have not examined how these parental views affect the child's help-seeking behavior and/or the ways in which the child views their own disorder. This is called "self-stigma," which is defined as the negative feelings towards oneself that are related to being ashamed or embarrassed about having mental health issues or a disorder (Corrigan & Matthews, 2003). Self-stigma could potentially be a contributing factor to low help-seeking rates for this demographic, which could be connected to the act of perceiving negative attitudes on mental health services from their parents (Arcia et al., 2002).

ADHD in Women

Women with ADHD are typically more likely to exhibit inattentive symptoms, which can look like daydreaming in class or not being able to follow along with conversation (Gershon & Gershon, 2002). Due to the differences in symptom presentation, it may be more difficult to identify ADHD symptoms in women, as the symptoms are much less external than in their male counterparts. Literature also demonstrates that women with ADHD are at a higher risk of participating in self-harm in adolescence as a result of the impulsivity that persists beyond childhood (Swanson et al., 2014). Women with ADHD are also prone to developing symptoms of anxiety and depression, which makes their assessment more complex. Not only is this population harder to identify and properly diagnose but they are also more likely to develop severe mental health issues the longer they go without treatment.

Acknowledging Intersectionality

Previous research has demonstrated that Latinx patients with ADHD are much less likely to receive a diagnosis early in life (Lawton et al., 2014). As a result, female patients with ADHD are also subjected to going without proper treatment until later in life (Swanson et al., 2014). However, there is not any research examining how intersecting identities of female Latinx patients with ADHD could potentially create a completely unique experience for the individual. In theory, Latina women with ADHD could be experiencing even lower levels of successful treatment outcomes in comparison to females of other racial/ethnic backgrounds with ADHD. This racial disparity could be connected to rates of enculturation and the stigmatization of mental health services, both of which are ultimately a result of familial relationships (Villatoro et al., 2014).

This study seeks to address the following research questions: 1) How are perceived parental attitudes on utilizing behavioral health services affecting help-seeking behavior in Chicanx/Latinx women with ADHD? 2) Are higher rates of enculturation positively associated with rates of stigma against mental health? 3) Are there any prominent indications of ADHD in this population? The results could potentially influence future psychoeducation and increase overall support for this understudied population.

Method

Design

This quasi-experimental study utilized a multi-method strategy. Researchers conducted qualitative interviews, which were designed to investigate interviewees' clinical experiences with ADHD symptoms, familial relationships, and prominent features of ADHD within this population. Participants were asked to reflect on their parents' attitudes on mental health and how those interactions have influenced their choice to seek or not seek help for their ADHD symptoms. Participants described how their ADHD symptoms affect their ability to complete coursework and their day-to-day tasks. As for quantitative methods, participants filled out a Likert-scale questionnaire based on how they perceive their parents to view mental health and traditionalism. The combination of qualitative and quantitative methods allowed for a more holistic approach to the research questions. Researchers had three separate hypotheses for the study. In response to the first research question, researchers hypothesized that participants who were diagnosed with ADHD would report more familial support in comparison to those who were symptomatic with no diagnosis. In response to the second research question, researchers hypothesized that participants who reported high rates of perceived enculturation rates in their parents would also report high rates of perceived stigma. Lastly, in response to the third research question, researchers hypothesized that the interviewed women will mostly demonstrate inattentive symptoms, high functioning behavior, and emotional dysregulation.

Participants

Researchers interviewed a total of eight participants (five of whom had a diagnosis and three of whom were symptomatic with no diagnosis. All participants identified as female and Chicanx individuals and were aged 18-24. The goal was to recruit subjects within this population who either have diagnosed ADHD or exhibit symptoms associated with ADHD. Participants from each group will be used as a comparison in order to assess for positive/negative factors affecting help-seeking behavior or lack thereof.

Measures

Qualitative

Participants were interviewed with a protocol consisting of 30 questions. The protocol was a mix of open and closed questions. The first half of the interview consisted of questions related to the individual’s symptoms and how those symptoms have affected their coursework/day-to-day activities. For example, one question asked, "Have you ever felt like you had to work harder than your peers to complete the same amount of work?" Next, interviewees were asked to reflect on their help-seeking behaviors and experiences navigating the behavioral health system. They were also asked to share their opinion on how to tackle the challenge of developing psychoeducation for their parents. For example, participants were asked, "Do you think your parents would have benefited from hearing from another Latinx parent who has a child with ADHD?" Lastly, the participants were asked to share details about instances where mental health issues were discussed with their family.

Quantitative

Participants were surveyed using the Day's Mental Illness Stigma Scale and the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults. The Day's Mental Illness Stigma Scale was utilized to examine how participants perceive their parents’ attitudes towards mental illness (Day et al., 2007). It has a total of 28 items, where participants were asked to rate if they completely disagree (1) or completely agree (7) with each statement. A higher score indicates that participants perceive their parents to demonstrate less stigmatizing attitudes towards mental illness. The scale has been validated to be used with college students and has previously been used to report on how individuals perceive others attitudes on mental health. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults—which has been validated for use within the Chicanx population—was used to assess levels of enculturation/acculturation (Knight et al., 2010). It contains a total of 50 items with questions that pertain to five categories: familism-support, familism-obligations, familism-referent, respect, traditional gender roles, overall Mexican values, material success, independence and self-reliance, competition and personal achievement, and overall mainstream values. Participants were asked to rate "how much they believe in" each statement on a scale from 1-5, 1 being not at all and 5 being completely. However, in the case of this study, they were only asked to reflect on how they perceived their parents would fill out the questions on each survey. Higher scores on this scale would indicate that participants perceive that their parents demonstrate a higher presence of enculturation as opposed to acculturation.

Procedure

Researchers reached out to various Latinx campus organizations to promote the study to their members on social media and during their events. This strategy was sufficient for recruiting the total number of eight participants for the study.

Once participants were recruited, they were contacted through email to coordinate a time to schedule a 1-1.5 hour qualitative interview over Zoom. Each participant was given an ID number in order to conceal their identity. The interview consisted of questions about their relationship with their parents, their parents' attitudes on mental health services, and how those factors have affected their help-seeking behavior. Once the participant consented, the interview was recorded over Zoom for the purpose of being transcribed and analyzed afterwards. Researchers disposed of the video footage and only kept the audio until the interviews were transcribed. Once the interviews were transcribed, the audio was deleted as well. After the participants finished the qualitative interview, they were given a 5-minute break and then given instructions on how to fill out the Qualtrics survey. Researchers read the Day's Mental Illness Scale prompt on the general mental illness condition, and participants were instructed to fill out both sections of the survey from the perspective of their parents. For each question, they were instructed to choose the answer they would expect their parents to fill out for both the Day's Mental Illness Stigma Scale and the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults. Participants were supervised over Zoom as they completed the survey, which was the last step in the study.

Analytic Approach

To analyze the qualitative data, all of the interviews were transcribed using AI software from Otter. Transcripts were broken up into sections of 3-5 sentences and placed into a Google Sheet. Each section was coded according to the Coding Key, which was developed throughout the first three transcripts between two coders. The Coding Key consisted of seven major themes represented throughout all of the participants, for a total of 56 individual codes. Two coders completed coding all eight interviews independently and then met to discuss any discrepancies afterwards. If the coders were not in agreement for a section, they would each explain their thought process for the coding until they could come to an agreement (though there were not many discrepancies).

To analyze the quantitative data, the participants' survey responses were recorded on Qualtrics and the data was exported to be coded in R-Studio. Researchers conducted a bivariate correlation, since the sample size was too small to run a correlation analysis.

Quantitative Results

Researchers conducted a bivariate correlation analysis through R-Studio, which compared the relationship between the participants' parents' perceived stigma towards mental health and perceived enculturation (adherence to traditional Mexican values). The participants were asked to report on how they perceived their parents would respond to the Day's Mental Illness Scale (measuring Stigma) and the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults (measuring Enculturation). To reiterate, a low score on the Day's Mental Illness Scale indicates less stigma towards mental health, and a high score on the enculturation measure indicates high levels of adherence to Mexican values. Due to the small sample size, only one significant result was found, but the variables demonstrated an overall trend of positive correlation with one another.

The Day's Mental Illness Scale scoring was organized into categories such as Treatability (faith in the efficacy of treatment), Professional Efficacy (trust in the expertise of mental health care professionals), and Anxiety (fear of those with mental illness). The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for Adolescents and Adults scoring was also organized into various categories of values, however this study focused on Familism Obligation (obligation to adhere to prioritize family), Respect (respecting elders), and Material Success (working towards a better financial state).

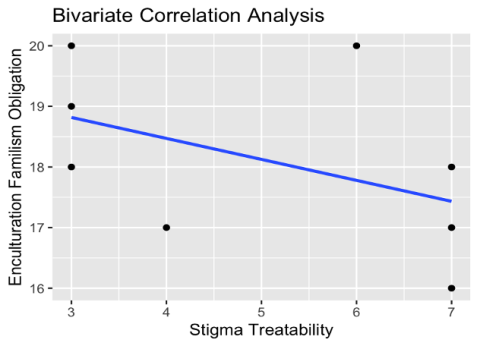

Pearson's product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between Treatability and Familism Obligation (t= -1.2608, p= 0.2542, 95% CI [-0.88, 0.36], N= 8) and the variables were not significantly correlated but did demonstrate a strong trend. A scatter plot summarizes the results (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Treatability and Familism Obligation

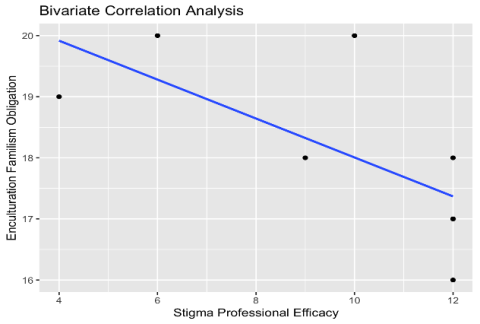

Pearson's product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between Professional Efficacy and Familial Obligation (t= -2.2753, p=0.06321, 95% CI [-0.94, -0.05] , N= 8) and they were not significantly correlated but still demonstrated a strong trend in the expected direction. A scatter plot summarizes the results (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Professional Efficacy and Familial Obligation

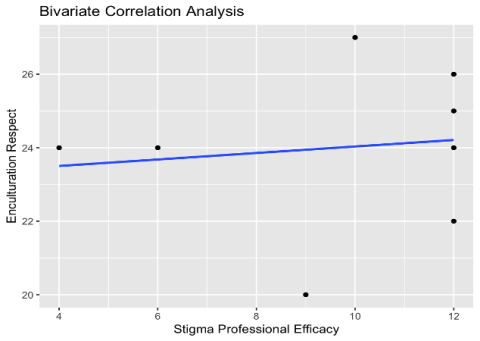

Pearson's product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between Professional Efficacy and Respect (t= 0.30835 , p=0.7682, 95% CI [-0.64, 0.76] , N= 8) and they were not significantly correlated and were not trending. A scatter plot summarizes the results (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Professional Efficacy and Respect

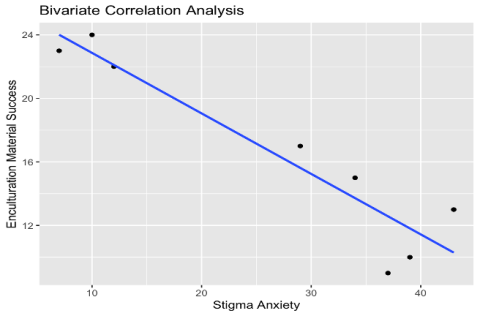

Pearson's product-moment correlation was used to assess the relationship between Anxiety and Material Success ( t= -6.6014 , p= 0.000581, 95% CI [-0.99, -0.69] , N= 8) and they were significantly negatively correlated in the expected direction. A scatter plot summarizes the results (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Anxiety and Material Success

Qualitative Results

Using the Coding Key, participants' responses were coded into accordance with seven major themes: Behavior, Mental Health, Emotions, ADHD Symptoms, Stigma, Action Items, and Cultural Factors. Interviews were broken up into sections of 3-5 sentences and then coded for the themes. For example, under the major theme of Behavior, there are three codes consisting of Lack of Time Management, Cycling Behavior, and Self-awareness.

Theme 1: Behavior

Participant responses were coded as one of three possible codes within this major theme: Lack of Time Management, Cycling Behavior, and Self-awareness. The purpose of this theme was to capture important behaviors that do not exactly fall under the category of ADHD Symptoms. Lack of Time Management was the most prominent code within this theme, followed by Self-awareness. For example, one participant indicated a Lack of Time Management by describing, "I forget due dates, I write them down all the time. But I just… I miss them… ADHD pushes me to do things... last minute." Self-awareness was often coded for when a participant explained how they became concerned with the possibility of having ADHD by acknowledging the abnormalities in their behavior.

Theme 2: Mental Health

Participant responses were coded as one of nine possible codes within this major theme: ADHD Diagnosis, Access to Health Care, No Access to Mental Health Care, ADHD Specific Counseling, No Culturally-Adapted Psychoeducation, Misinformation on ADHD, Psychoeducation Importance, Genetics (ADHD trend within the family), and Negative Experience (with receiving mental health care services). The most prominent codes were Genetics, Psychoeducation Importance, and No Culturally-Adapted Psychoeducation. ADHD has been known to be a hereditary disorder (National Institutes of Health, 2020), and the participants who did report instances of the disorder within their family often shared that it was identified in male individuals. More importantly, two out of three participants who did not have a diagnosis reported that their brothers were diagnosed with ADHD. One participant shared that her parents invalidated her concerns of ADHD symptoms by saying, "You can't really have ADHD because… you don't have hyperactivity." This idea will be expanded upon within the Stigma theme. When analyzing Psychoeducation Importance, researchers found that every participant was in support of prioritizing psychoeducation for Latinx individuals with ADHD. One participant explained that psychoeducation on mental health care in general is important: "Most of the times when it's people that come from POC backgrounds… you don't know what the process of these things [mental health care processes] are." This goes hand in hand with the code of No Culturally-Adapted Psychoeducation, which captures the participants' expressed concerns for lack of culturally competent care. Participant 7 described the complexity of the issue by explaining, "My mom kind of sees it as like meaning [of mental health disorders] kind of lazy… or trying to make it seem like I’m making more problems for myself." In other words, the participant shared that Latinx families need extra support when it comes to addressing their cultural concerns with the mental health care system.

Theme 3: Emotions

Participant responses were coded as one of five possibilities: Stress, Self-Stigma, No Self-Stigma, Test Anxiety, and General Anxiety. The most prominent codes were Stress, Self-Stigma, and No Self-Stigma. Many participants reported feelings of stress in times of procrastination or when falling behind on coursework. Participant 5 shared a stressful memory from her childhood: "I remember… sitting there and crying in fifth grade. Because I felt like I had so much homework." Self-Stigma can be described as feelings of shame or embarrassment about one's mental disorder, which, in this case, is ADHD. Participant 4 explained that they feared others wouldn’t treat them the same if they knew they had ADHD: "Or they might… ask me more repeatedly, 'Do you get this? Do you understand what I'm saying?'" On the other hand, No Self-Stigma was coded for in the event that a participant demonstrated a lack of acceptance for their disorder. For example, Participant 1 shared that their diagnosis actually provided them with a sense of relief as they now "have a better understanding" of their behaviors.

Theme 4: ADHD Symptoms

Participant responses were coded as one of 12 possibilities: Careless Mistakes, Time Blindness, Impulsivity, Inattentive, Hyperactive, Procrastination, 2x Peers (having to work twice as hard to complete the same amount of work), Comorbidity, Emotional Dysregulation, Burnout, Racing Thoughts, and Academic Struggles. The most prominent codes were Careless Mistakes, Inattentive, 2x Peers, Academic Struggles, and Burnout. All of the participants expressed concern for the trend of Careless Mistakes within their course work. Participant 6 explained, "Little mistakes can affect us a lot," and described a time where she miscalculated and wrote her answer backwards on a calculus exam. Even though she had the correct answer originally, she ended up losing 5 points on the final exam. The Inattentive code was by far the most utilized within the theme and was one of the most frequently used codes among all themes. Participant 2 shared that they typically are easily distracted and often find themselves "daydreaming while doing homework." A majority of the participants coded for 2x Peers, as they expressed feeling as if they often fell behind in academic abilities in comparison to their neurotypical peers. Participant 1 shared that one quarter, she had the same schedule as her roommate and felt as if "she [the roommate] could just get through readings so fast, and just understand them so well" in comparison to herself. Lastly, Academic Struggles was mentioned by all of the participants in a range of moderate to severe rates. Participant 4 explained that they often "take longer to grasp concepts… [and] it takes at least two to three weeks just to cover one topic" for her to fully understand the class material. Lastly, Burnout was often experienced by participants who were overextending themselves to function at the same level as their peers. Participant 7 shared that sometimes they "just don't have the motivation to do anything… I'm just feeling fatigued all the time, like tired… unmotivated." Overall, these were the most common and powerful demonstrations of ADHD symptoms within the participants.

Theme 5: Stigma

Participant responses were coded as one of four possible codes: Familial Stigma, Hyperactive Dominant Stigma, Concerns Invalidated, and Medication Stigma. Familial Stigma was utilized to code for any instances of stigma towards mental health demonstrated by the participants’ family members, which was one of the most utilized codes over all of the themes. One memorable instance of Familial Stigma was when Participant 1 explained how her parents reacted to a cousin who was experiencing mental health issues: "'There's nothing wrong with her, like, she's fine. Her parents make good money, they give her a good home'… assuming that because she had everything perfectly good on the outside, that she would be perfectly fine on the inside." By contrast, Hyper Dominant Stigma focuses on the idea that only men, who exclusively exhibit hyperactive symptoms not commonly seen in women, can suffer from ADHD. Participant 5 shared that when a therapist expressed concerns of ADHD symptoms at age 12, her "parents laughed it off" and said, "Oh, that's for boys who can't sit down, ADHD is strictly for boys." The purpose of the Concerns Invalidated code is to encompass the kind of negative feelings that come as a result of brushing off ADHD concerns due to Hyper Dominant Stigma. As a result of being invalidated, Participant 5 shared, "I felt like I had a lot of those symptoms. So I just felt invalidated by a bad experience." In a time when she needed extra support, her parents instead chose to overlook her concerns as well as a professional opinion. The Medication Stigma code was created to explain how Latinx parents may feel uncomfortable with the idea of psychotropic medication, which then influences their children's choices to utilize medication or not. Participant 6 shared that they felt "embarrassed" about having to "take a pill to get through my day" and feared the possibility of addiction.

Theme 6: Action Items

Participant responses were coded as one of nine possible categories: Utilizing Teachers, Holistic ADHD, School Psychologists, Parent Peer Mentoring, Inclusivity, Support System, Communication, Accommodations, and Educational Flyers. The most prominent codes were Utilizing Teachers, Inclusivity, Support System, and Communication. The overall theme of Action Items exists to investigate how the clinical experience can be improved for this marginalized group. All of the participants came to the consensus that Utilizing Teachers would be a great course of action for a warm handoff to mental health care services, as parents often feel more comfortable communicating with teachers rather than mental health professionals. Participant 3 shared that it is especially useful for parents to connect with "bilingual staff", who will ultimately help them understand the complexities of ADHD in their child. The next important code was Inclusivity, which prioritizes providing culturally adapted care with an emphasis on psychoeducation for Latinx patients and their families. Participant 5 shared that her parents could have benefited from "a support group managed by therapists" to provide psychoeducation on ADHD and how it manifests in Chicanx women. Support systems were found to be very important for these women as they navigated the mental health care system and their disorder. One participant shared that even though her parents knew they weren't knowledgable about mental health issues, they still encouraged her to "get the help that she needed." She went on to express how this was a "rewarding and motivating experience." Lastly, Communication was one of the most utilized codes within this theme because of its power to change negative attitudes on mental health. Participant 2 shared that her parents didn’t think mental health issues were "real" but over time, talking about mental health issues helped them to "become more understanding." Communication about mental health helps to normalize this typically taboo topic within the Latinx community.

Theme 7: Cultural Factors

Participant responses were coded as one of four possible categories: Use of "Crazy," Distrust, and Parent Attitudes Evolving. One of the most moving codes—Use of "Crazy"—demonstrated how exhibiting stigma towards those struggling with mental health issues can damage the parent-child relationship. Participant 3 shared that her family referred to her great-grandmother, who was suffering from schizophrenia, as "crazy" and would "treat her as less than a person." She went on to explain how this made her uncomfortable and contributed to her reluctance to seek out help from mental health care services. Another common trend seen within the Latinx community is distrust of the mental health care system, which is where the creation of the Distrust code stemmed from (Villantro, 2014). Participant 5 explained how her father prohibited her from receiving therapy because "he thought that therapy was for crazy people." This demonstrates how distrust in the mental health care system can make treatment retention rates difficult to keep up. On a more positive note, Parent Attitudes Evolving exists to capture how many participants shared that, over time, their parents became more comfortable with mental health and mental health support services. Participant 3 shared that once one of her cousins was diagnosed with ADHD, her parents, who originally were against utilizing mental health care services, realized that "if you're not getting the help you need, it can progressively get worse."

Discussion

Interviewing these eight participants has provided researchers with new insight on the unique experience of being a Chicana with ADHD. It was predicted that participants who were diagnosed with ADHD would report more familial support in comparison to those who were symptomatic with no diagnosis. The three participants who were symptomatic but did not have an ADHD diagnosis expressed more instances of Familial Stigma and overall lower levels of support, which was consistent with the initial hypothesis. In comparison, the participants who felt supported by their family members were able to take the necessary steps to receive the help they needed from mental health care. This demonstrates the importance of prioritizing culturally adapted psychoeducation, as families who have a better understanding of ADHD will feel more comfortable supporting the patient through navigating the mental health care system (Kopelowicz et al, 2012). Though this phenomenon is not typically taken into consideration in the West, collectivist culture for Chicanx individuals relies on feelings of familial support in order to feel comfortable seeking out help from mental health care services (Hirai et al., 2015). Another important contributing factor to low help-seeking rates within this demographic is stigma and its connection to enculturation rates.

In order to examine the relationship between the participants' clinical experiences and their parents' perceived attitudes, participants were asked to report on their parents' perceived rates of enculturation and mental health stigma. Researchers predicted that participants who reported high rates of perceived enculturation rates in their parents would also report high rates of perceived stigma. The purpose of investigating these variables was to supplement the stories of familial stigma throughout the participants' lives. Although only one of bivariate correlational relationships demonstrated significance, two out of the four were trending towards predicted directions. The significant relationship between the perceived parental attitudes of 1) Stigma: Anxiety (or feelings of discomfort) towards those with mental health issues and 2) Enculturation: Material Success demonstrates that there is a connection between familial stigma and stigma towards mental health. Unfortunately, Chicanx parents who exhibit higher rates of Enculturation within this category are also prone to demonstrating higher levels of Stigma towards mental health. Parental attitudes like these can make the process all the more difficult for participants who are in need of support from mental health care services. Traditionalism within the Chicanx community—often directly connected with Enculturation—is hurting women who are suffering from ADHD symptoms but do not feel comfortable seeking out professional help due to fear of being judged by their family (Villatoro et al., 2014). This is especially difficult for these women of color, as they are also faced with Hyper Dominant Stigma, which invalidates Chicanx women with ADHD by exclusively classifying the disorder with hyperactive symptoms typically seen in women. All of these factors should be taken into consideration when creating psychoeducation material for Chicanx populations and for clinicians working with this demographic.

Lastly, researchers predicted that these women would demonstrate mostly inattentive symptoms, high functioning behavior, and emotional dysregulation. As stated in the results, the most commonly reported ADHD symptoms fell under the Inattentive code. Inattentive symptoms can include daydreaming, forgetfulness, and struggling to stay on/switch between tasks (APA, 2013). The fact that these women reported a presence of mostly inattentive ADHD symptoms indicates that they have the ability to overcompensate for their short-comings by working harder than their peers. Many participants reported "overwhelming feelings of stress" and "burnout" as a result of trying to constantly play catch up with course material due to their ADHD symptoms. This kind of high functioning behavior leaves participants—who struggle with a disorder that prohibits them from performing at the same levels as their peers—vulnerable to emotional dysregulation.

Limitations

The most prominent limitation to the study is the small sample size. Evaluating only eight participants limited the researchers' ability to produce significant results, even if the variables demonstrated positive trends. Not being able to personally interview the parents of the participants and only collecting information by way of participants’ perceived parental attitudes/behavior was another limitation. Future research should prioritize interviewing both parents and children in order to gain a better understanding of how culture and family dynamics affect the help-seeking behavior and clinical experience of Chicanx women with ADHD.

Conclusion

Chicanx women with ADHD, and women of color in general, are an understudied population that need to be prioritized by researchers in order to improve quality of care. Latinx populations are at risk for developing severe mental health issues in general due to cultural factors, and women with ADHD are especially vulnerable to comorbidity if untreated (Kataoka et al., 2002). Clinicians should take these results into consideration when evaluating Chicanx women for ADHD symptoms, as prioritizing multicultural aspects can make all the difference when treating patients from collectivist backgrounds. These women should also be equipped with knowledge on how their disorder uniquely affects them, as well as provided with resources on how to effectively communicate with their families about ADHD/overall mental health. Taking these extra precautionary measures can create an improved clinical experience for this marginalized population, which can then lead to better outcomes for the patients' wellbeing. Overall, researchers urge the field of clinical psychology to continue advocating for culturally sensitive care and investigating the best ways to implement it into clinical practice in the status quo.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:59–61.

Arcia, E., Sánchez-LaCay, A., & Fernández, M. C. (2002). When worlds collide: Dominican mothers and their Latina clinicians. Transcultural Psychiatry, 39(1), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150203900103

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 9). Data and statistics about ADHD. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 25). About mental health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm

Corrigan, P. W., & Matthews, A. K. (2003). Stigma and disclosure: Implications for coming out of the closet. Journal of Mental Health, 12(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963823031000118221

Day, E. N., Edgren, K., & Eshleman, A. (2007). Measuring stigma toward mental illness: Development and application of the mental illness stigma scale 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(10), 2191–2219.

Gershon, & Gershon, J. (2002). A Meta-Analytic Review of Gender Differences in ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 5(3), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470200500302

Grimm, O., Kranz, T. M., & Reif, A. (2020). Genetics of ADHD: What should the clinician know? Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7046577/

Hirai, M., Vernon, L. L., Popan, J. R., & Clum, G. A. (2015). Acculturation and enculturation, stigma toward psychological disorders, and treatment preferences in a Mexican American sample: The Role of Education in reducing stigma. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3(2), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000035

Johannessen, J. O., McGlashan, T. H., Larsen, T. K., Horneland, M., Joa, I., Mardal, S., ... & Vaglum, P. (2001). Early detection strategies for untreated first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 51(1), 39–46.

Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–1555.

Knight, G. P., Gonzales, N. A., Saenz, D. S., Bonds, D. D., Germán, M., Deardorff, J., ... & Updegraff, K. A. (2010). The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(3), 444–481.

Kopelowicz, A., Zarate, R., Wallace, C. J., Liberman, R. P., Lopez, S. R., & Mintz, J. (2012). The ability of multifamily groups to improve treatment adherence in Mexican Americans with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(3), 265–273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.135

Lawton, K. E., Gerdes, A. C., Haack, L. M., & Schneider, B. (2014). Acculturation, cultural values, and Latino parental beliefs about the etiology of ADHD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0447-3

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Brody, D., Fisher, P. W., Bourdon, K., & Koretz, D. S. (2010). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among U.S. children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics, 125(1), 75–81.

Swanson, E. N., Owens, E. B., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2014). Pathways to self‐harmful behaviors in young women with and without ADHD: A longitudinal examination of mediating factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(5), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12193

Villatoro, A. P., Morales, E. S., & Mays, V. M. (2014). Family culture in mental health help-seeking and utilization in a nationally representative sample of Latinos in the United States: The NLAAS. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(4), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099844

Zvolensky, M. J., Rogers, A. H., Mayorga, N. A., Shepherd, J. M., Bakhshaie, J., Garza, M., ... & Peraza, N. (2022). Perceived Discrimination, Experiential Avoidance, and Mental Health among Hispanic Adults in Primary Care. Transcultural Psychiatry, 59(3), 337–348.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

1. If you were diagnosed later in life...

a. Can you think of a specific moment (memory) when you seriously thought you might have ADHD?

b. If not then please explain how you became concerned with the possibility of having ADHD?

2. Do you have an official diagnosis?

a. If so please describe what steps you took to receive the initial diagnosis (if you remember).

b. If you can’t remember because you were diagnosed early in life, what have your parents reported to you?

c. If you do not have a diagnosis, are there any obstacles keeping you from receiving the support you would like?

3. What kind of support would you like to receive for your ADHD symptoms?

4. How do you think your ADHD symptoms were present as a child?

5. Do you feel you often make careless mistakes (in your coursework)? This can be at any point in time of your educational experience.

6. How does ADHD negatively impact your ability to succeed in your courses?

7. Have you ever felt like you had to work harder than your peers to complete the same amount of work?

8. Do you believe that you could have benefited from universal screening for behavioral health issues throughout your k-12 educational experience?

9. Did anyone in your life ever discourage you from seeking support for your concerns?

10. Do your parents know you have an ADHD diagnosis? If you were diagnosed later in life, how did you tell your parents you had ADHD?

11. If you had to describe your parents' understanding of the disorder, what would you say?

12. Do you believe it would have been beneficial to describe ADHD as a health issue rather than a mental disorder?

13. What do you think is the best way to educate Latinx parents on ADHD?

14. Do you think your parents would have benefited from hearing from another Latinx parent who has a child with ADHD? As far as sharing their experiences with treatment and how it has benefitted their child

15. Do you think they would be a receptive on-going support group for Latinx parents with children who have ADHD?

16. Do you think it would be helpful to utilize counselors/teachers in schools as the middleman between parents and the behavioral health care system?

17. Are there specific memories you have of your parents discussing mental health? What are your parents' attitudes towards people who utilize mental health care services?

18. Have your parents ever called someone who was struggling with mental health issues “crazy”?

a. If so, how did that make you feel?

19. Do they utilize mental health care services themselves?

20. Would you say that your parents treat people with mental health issues differently? Please describe how they act towards them (e.g., tone, body language, wording).

21. Is there anyone in your family that has openly shared that they utilized mental health care services?

a. If so, what do your parents think about their help-seeking behavior?

22. How have your parents treated you while you navigated the mental health care system?

23. If you have a diagnosis, do you utilize medication?

a. Do you find utilizing medication helpful?

b. If you do not have a diagnosis, would you be interested in utilizing medication?

24. What do your parents think about you utilizing medication for ADHD?

25. Did /do you have any fears/concerns about using medication?

26. Have you ever felt embarrassed/ashamed about utilizing medication?

27. Do you fear that others would judge you if they knew you have ADHD?

28. Have you ever felt embarrased/ashamed of being labeled as someone with a neurodivergent disorder?

29. Do you fear that others would treat you differently if they knew you had ADHD?

30. Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience as a Chicana/Latina with ADHD/ADHD symptoms?